I keep an eye on vulnerability reports for WordPress plugins, always trying to learn more about plugin security. As a plugin developer myself, it is important to learn about pitfalls so that I don't make the same mistakes in my own plugins.

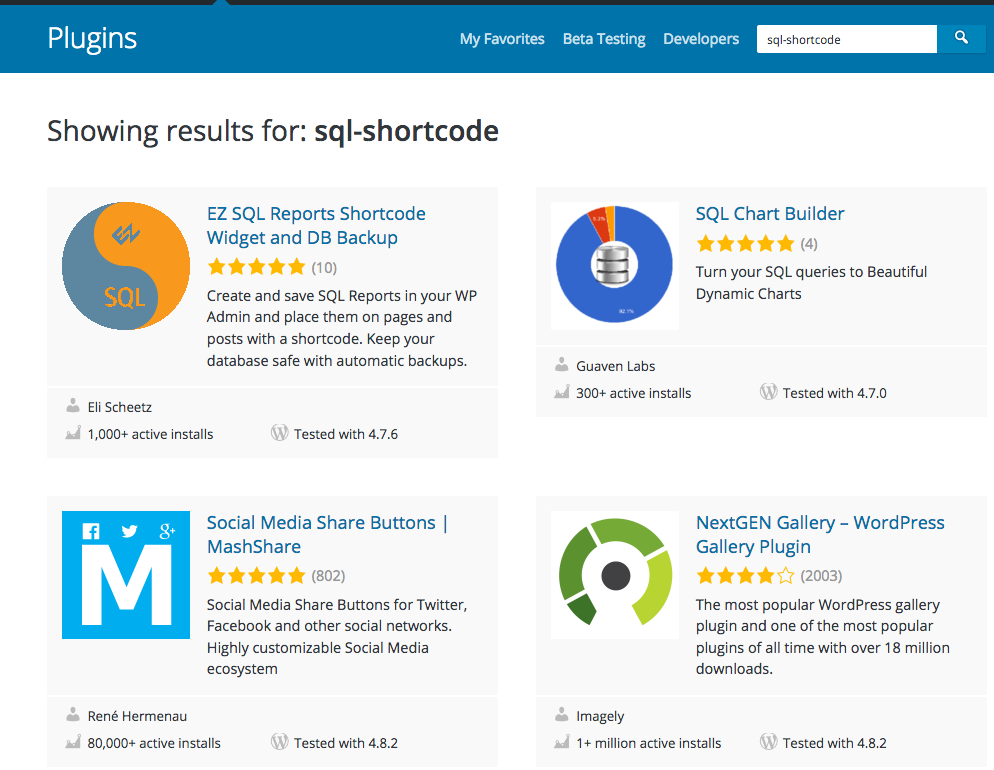

A while ago I saw a report for a plugin that provided a shortcode for executing SQL queries. Providing a feature like that in a shortcode is problematic, because any user can execute a shortcode on the site, as long as they are logged in.

The details of why that is possible were first explained (to my knowledge) in this vulnerability report put out by Securi. The short story is that WordPress core includes an Ajax callback for the parse-media-shortcode action that does just what its name sounds like: it parses shortcodes (and not just media shortcodes either). Because that action is not protected by any capability checks, it is possible for any logged in user to pass a shortcode to it in the shortcode parameter, and it will be executed.

In the case of the plugin offering a shortcode that ran an SQL query, this meant that any user of the site could run any SQL query that they wanted to. Like this, for example:

[[sql]SELECT user_email, user_pass FROM wp_users[/sql]]For some reason, I clicked through the link in that report to see if the plugin was still available on WordPress.org. It wasn't, but the plugin directory automatically provided helpful results for similar plugins.

The first result was the EZ SQL Reports Shortcode Widget and DB Backup plugin. A look at the plugin's page revealed this:

There is also an shortcode for the wpdb::get_var function that you can use to display a single value from your database. For example, this will display the number of users on your site:

[sqlgetvar]SELECT COUNT(*) FROM wp_users[/sqlgetvar]

Uh oh. Here we have another plugin that allows arbitrary SQL to be run via a shortcode.

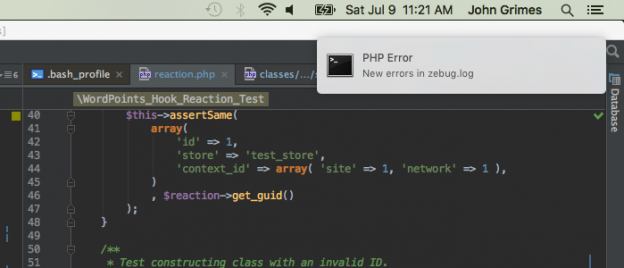

To make sure that things were actually as bad as they seemed, I took a look at the code. As it turns out, things weren't as bad as they seemed. They were worse.

function ELISQLREPORTS_get_var($attr, $SQL = "") {

global $wpdb;

if (!is_array($attr)) {

if (strlen($attr) > 0 && strlen($SQL) == 0)

$SQL = $attr;

$attr = array("column_offset"=>0, "row_offset"=>0);

} elseif (isset($attr["query"]))

$SQL = $attr["query"];

if (!(isset($attr["column_offset"]) && is_numeric($attr["column_offset"])))

$attr["column_offset"] = 0;

if (!(isset($attr["row_offset"]) && is_numeric($attr["row_offset"])))

$attr["row_offset"] = 0;

$var = $wpdb->get_var(ELISQLREPORTS_eval($SQL), $attr["column_offset"], $attr["row_offset"]);

if (isset($_GET["get_var"]) && ($_GET["get_var"] == "debug") && !$var && $wpdb->last_error)

return $wpdb->last_error;

else

return $var;

}

add_shortcode("sqlgetvar", "ELISQLREPORTS_get_var");

Yes, the ELISQLREPORTS_eval() function is as bad as it sounds.

function ELISQLREPORTS_eval($SQL) {

global $current_user, $wpdb;

if (@preg_match_all('/<\?php[\s]*(.+?)[\s]*\?>/i', $SQL, $found)) {

if (isset($found[1]) && is_array($found[1]) && count($found[1])) {

foreach ($found[1] as $php_code)

eval("\$found[2][] = $php_code;");

$SQL = $wpdb->prepare(preg_replace('/<\?php[\s]*(.+?)[\s]*\?>/i', '%s', $SQL), $found[2]);

}

}

return $SQL;

}

Not only is there the potential for arbitrary SQL execution, but the shortcode also provides another special feature: it allows arbitrary PHP to be embedded as well! (Although notice the care to try and prevent SQLi by using $wpdb->prepare() 😃.)

Remember, shortcodes can be executed not just by anybody who can edit a post (which would include Contributors), but also by even Subscriber-level users using the admin-ajax.php trick explained out above. This means that any user on a site can use the shortcode provided by this plugin to execute arbitrary SQL and PHP in the context of the site.

A PoC using the example shortcode:

<form action="http://src.wordpress-develop.dev/wp-admin/admin-ajax.php" method="post">

<input name="action" value="parse-media-shortcode"/>

<input name="shortcode" value="[sqlgetvar]SELECT COUNT(*) FROM wp_users[/sqlgetvar]"/>

<input type="submit" value="Execute SQL!"/>

</form>

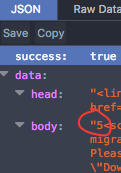

Log in as a subscriber, submit the form, and viola!

parse-media-shortcode action.The next step was to try and contact the plugin developer. First, I looked at the plugin's page in the plugin directory, to see if there was a contact method mentioned anywhere. I then went to the plugin author's profile to see if they had a contact listed there. They did have a website listed, but I couldn't find any means to contact them through that.

The only remaining option appeared to be to attempt to contact them through a direct message on WordPress's Slack. When that didn't get a response, I later remembered to also check in the plugin's code, as often an email address is included in the copyright notice. Fortunately, that was the case, so I sent an email to that address.

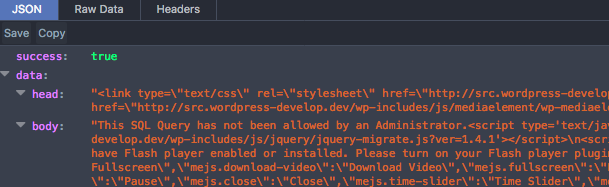

Within 24 hours I received a response, and soon after version 4.17.38 was released. It mitigates the issue by only allowing SQL to be used in the shortcode that matches one of the SQL reports created using the report creation feature offered by the plugin. A note regarding this was added to the plugin readme:

Note: because of a recently discovered exploit in the WordPress shortcode functionality it is now required that an admin user create an SQL Report with the exact query that will be used in the sqlgetvar shotcode, otherwise any subscriber could white their own shortcode query.

This means that you can no longer execute arbitrary SQL. If you provide a query not already available as an SQL report, you'll just get the error "This SQL Query has not been allowed by an Administrator."

Because SQL reports can only be created by a user with the 'activate_plugins' capability, this should sufficiently mitigate the issue.

The big takeaway here is that you need to be very careful what you make possible via a shortcode. Plugin authors have been able to get by with some things in shortcodes that shouldn't really be there, because historically at least shortcode execution was usually only possible for Contributor-level users and up. But with the introduction of wp_ajax_parse_media_shortcode() in WordPress 4.0, vulnerabilities in shortcodes are now exposed to even Subscriber-level users, making any site that allows user registration immediately exploitable if a shortcode is vulnerable.

This is a point where the plugin community needs some education, and where perhaps core should even consider placing more restrictions on this Ajax action to mitigate these issues (though vulnerabilities like these in shortcodes would still be exposed to anybody who could edit posts). I did bring this up with the security team, and they said that they do have plans to add more restrictions to the parse-media-shortcode Ajax callback in the future.

But until then, remember: Anything that a shortcode can do, any logged in user can do.